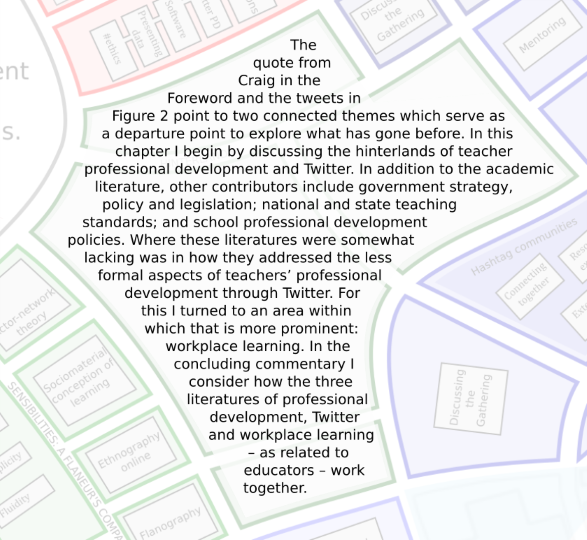

Given the continuing references to the city through the flanography, titling what might normally be called the literature review as ‘Hinterlands’ seemed more appropriate. For a city the hinterland is the region surrounding it which sustains and supports it, but which is itself influenced by the city. Supporting and sustaining my study are the literatures which precede and inform it, but to which I hope my study will also contribute. I refer to hinterlands in the plural since they are not only the inscribed outcomes of previous research, but include the methods which were employed to bring them into being, but I shall discuss them at greater length in a later post.

Professional development

Having experience of Twitter prior to commencing the study meant I was well aware of plenty of quotes similar to Craig’s in the preceding post and they which provide targets to explore. The first is professional development, though as I mentioned in a previous post, teachers phrase this in different ways and it is not clear that they may be referring to different things. This is to some extent mirrored in the literature so I begin by exploring how professional development and professional learning are distinguished and defined, only to discover that a commonly shared understanding has proven somewhat elusive. It is possible however, to to identify a wide variety of forms of professional development including, but not limited to: workshops, conferences, INSET days, classroom visits/observations, mentoring, coaching, reading professional literature, curriculum planning, self-evaluation, team teaching, involvement in working groups, accredited qualifications, learning networks with other schools. Although varied in nature – and probably in execution – these activities are largely structured, planned in advance, and mostly directed by someone other than the teacher involved.

Whatever form PD takes, one of its principal purpose is to improve pupil outcomes by enhancing teachers’ knowledge, skills, attitudes and practice, though this might sometimes be achieved through more oblique initiatives such as improving teacher morale or enhancing collegiality. Different paradigms have been proposed through which the changes might be conceptualised, some of which arise from within the individual (‘professional growth’ or ‘problem solving’) and others which are more likely to be externally mandated (‘deficit’ or ‘educational change’). This may lead to political tensions between individuals’ aspirations and the goals and targets of organisations and national systems. The range of interwoven factors becomes apparent, making alignment of individual, institutiional and systemic increasingly challenging.

One area of research which has received much attention is in establishing those factors which contribute towards PD being considered effective. Large-scale projects undertaken as the new millenium unfolded helped the community move towards consensus and agree on several characteristics associated with effective PD:

- Content focused.

- Involves active participation.

- Requires sustained engagement.

- Supports collaboration.

- Uses models of effective practice.

- Provides coaching and expert support.

- Offers feedback and reflection.

(Darling-Hammond et al, 2017)

There are those who argue however, that merely ensuring these characteristics are present will not necessarily lead to the desired outcomes. A simple process-product logic is inadequate for such a complex phenomenon and instead we should acknowledge the multiplicity of variables, interactions and effects, and difficulty in predicting outcomes.

When PD is effective, benefits can accrue at three levels; those of the pupil, the teacher and the school, though once again, these are interlinked rather than separate. Enhanced teacher knowledge, skills and practice tend to be located within the ‘occupational’ domain and are more prominent within the research. However, PD initiatives located in the ‘personal’ and ‘social’ domains may produce more affective benefits such as improvements in teacher attitudes, beliefs, commitment, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and morale. How these more therapeutic benefits influence teaching and pupil learning is far from easy to establish or predict.

In the next section I discussed the literatures which have explored Twitter; clearly an emerging and less mature field.

I begin by considering how research in this area began by describing what Twitter is in general terms and how different people come to Twitter for different reasons: daily chatter, sharing information, conversation and dialogue, reporting news, advertising and marketing, crowd-sourcing, collaboration and exchange, seeking help and support. As Twitter began to grow, it drew more research attention, and this became increasingly specialised, spanning disciplines including business, communication, education, emergency, geography, health, libraries, linguistics, search and security. Although research into educational uses of Twitter constitutes a small proportion of the whole (3-4% of the whole), that which focused particularly on teacher professional development is an even tinier fraction of that. My search strategy revealed only thirty articles on the topic, although I chose to limit the notion of ‘teacher’ to just those working in the sectors serving the needs of pupils in primary and secondary education.

Teachers are drawn to Twitter for a number of reasons including keeping up to date, accessing diverse perspectives, seeking support, reducing isolation, exchanging resources and ideas, and connecting with like-minded peers. The capacity to personalise the experience to suit their own needs is important to many, in the way they can choose the time, place and duration of their involvement. Drawbacks were also noted, such as the limited space (140 characters at the time), the potential for occupying an echo chamber, and the way in which anytime access might further eat into personal and family time.

The methods adopted in producing this body of research were drawn from a rather limited palette of surveys, interviews and collecting tweets. Only one study was broadly ethnographic in nature (Wesely, 2013) and none took a sociomaterial perspective. In reading across these papers, it was also clear that the research tended to frame their studies largely in relation to professional development or professional learning, sometimes conceptualised through communities of practice (or inquiry) or personal learning networks. With none taking a sociomaterial perspective, and participant observation being rare, there were clear gaps to be filled, but I also felt these studies might be relating their findings to the literature dealing with more formal, structured PD programmes. For that reason, I turned to a different hinterland to see what it might offer in terms of less structured, less formal learning.

Learning in the workplace

Deploying this body of literature when discussing teacher learning is far less common, but given the informal nature of the experiences described in the Twitter PD literature, perhaps this might offer an alternative lens. Workplace learning occurs at the intersection between working and learning; it is not a separate event or practice from either. It can include: reading professional literature, observation, collaboration with colleagues, reflection, learning by doing/through experience, browsing Internet and social media, experimenting, trial and error, talk with others, sharing materials and resources, and storytelling. Like the PD literature, a clear and consistent definition is elusive, but one way workplace learning can be framed is using either a metaphor of acquisition or of participation. In the former, something such as skills, knowledge or experience is gained, shared or applied. The latter is less about accumulation and reaching an endpoint, and is instead about ongoing active involvement in a particular context. The point is not that one is preferred over the other, but that both may be appropriate in different circumstances. I discussed this and other ways to conceptualise workplace at much greater length in an earlier post.

Elements of formality and informality are present throughout workplace learning, but once again being able to distinguish clearly between formal and informal learning is somewhat contested. Other terms such as non-formal, semi-formal and incidental have been added where learning practices might be neither entirely formal nor informal, suggesting a continuum, rather than a binary. Presence or absence of different characteristics are thought to help in classifying learning practices: whether there are learning objectives; where the locus of control lies (learner or someone else); duration (intermittent/continuous); whether the experience involves certification; whether the participant had intent or awareness of the learning; and location (specified/flexible). It has been suggested however, that learning in the workplace is often manifest as somewhat hybrid in which aspects of formality or acquisition are interwoven with professional practice, or as Baker-Doyle & Yoon (2011) put it:

While teachers may individually gather information at a professional development workshop, it is through their informal social network that this information is interpreted, shared, compiled, contextualized and sustained.

This might be one way in which Twitter PD plays a role.

Commentary

As I mentioned earlier, some teachers describe their activity on Twitter as PD, and as such naturally suggested one avenue for exploration. One might argue however, that despite teachers calling it PD and despite some elements of PD (as described in the literature) being present, perhaps this is something new, something which needs a different framing. Whether PD or workplace learning or something else is chosen as an appropriate hinterland, it is important to remember that they will produce a reality of Twitter PD in their own image. By this I mean that, if one goes looking for evidence of characteristics of professional development, then one is arguably more likely to find it. TPD displays only some of the characteristics associated with formal PD programmes, yet nor does it take place physically in the workplace. If what is taking place on Twitter is an entirely new form of professional learning, then considering previous hinterlands may be less likely to reveal those new practices. . There may be strands that can be drawn from both to form a more eclectic hinterland, or as Law (2004) put it; ‘try to reorganise the hinterlands to generate one that is new.’ One way this might be achieved is adopting an approach which encourages different methods to emerge, thereby destabilising the hinterlands which have thus far contributed. I begin that process in the next chapter by turning to actor-network theory as a source of disruption and consider how learning might be conceived when adopting a sociomaterial sensibility.

Baker-Doyle, K., & Yoon, S. A. (2011). In search of practitioner-based social capital: A social network analysis tool for understanding and facilitating teacher collaboration in a US-based STEM professional development program. Professional Development in Education, 37(1), 75-93. doi:10.1080/19415257.2010.494450

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev

Law, J. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research Routledge.

Wesely, P. M. (2013). Investigating the community of practice of world language educators on twitter. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(4), 305-318. doi:10.1177/0022487113489032

Really enjoying reading these posts, find myself agreeing, but also learning from your analysis. I’ve wrestled with these ideas of informal vs formal learning and definitions, to me anyway, seem to place a metaphorical straight-jacket around the deeper purpose of understanding. The paradox is that the evidence suggests ‘good’ PD requires structure, where both input and output can be clearly measured, but informal learning can lack the structure to be measured. But then, are there other ways to measure success of PD… such as through teacher contentment or self-actualisation?

LikeLike

Thanks for dropping by Richard.

I think measuring success or effectiveness is problematic for all sorts of reasons, at least in the context of teacher PD. I understand why some would think it necessary, but am not convinced we have the right ‘metrics’ yet. Just because we can measure it … yada yada. You mentioned a couple of alternatives that are clearly important. I don’t doubt that these connect back to outcomes such as pupil success, but I guess establishing correlation is the tricky part … if indeed that’s necessary at all.

LikeLike

[…] I explored how other had dealt with ethics across the thirty published papers I mentioned in Hinterlands. I was surprised to find that very few even mention ethics, let alone discuss it and in only one […]

LikeLike

Aaron Davis: mentioned this in 📰 Read Write Respond #035. via collect.readwriterespond.com

LikeLike

[…] it departed from the ‘messy’ thread I’d advocated throughout the rest of the thesis); how I articulated the literatures and how sociomaterial thinking informed that; the third Gathering and whether addressing the […]

LikeLike